A pathologist is a doctor who specializes in diagnosing diseases by looking at tissue from the body. You will probably never meet the pathologist, but samples of your colon tissue that are removed during surgery or biopsy will be sent to them for review.

The pathologist prepares a report of their findings. This is called the pathology report. This report has important information about your tumor and helps guide treatment decisions. You should request a copy of this report and keep it in your files.

Pathology reports may differ depending on which lab and doctor write it. In general, the report contains:

To help you better understand your report, let's go through these sections one at a time.

This is a description of the sample that the pathologist received and what they see with the naked eye. In a biopsy, the sample is likely a small piece of tissue, in which case the pathologist may describe the color, shape, feeling, and size of the tissue. After a cancer surgery, multiple organs or tissues may be sent to the pathologist and described in the report. This might include size, color, and weight. For example, a colon sample from a colectomy may be described as:

"Sample #1 is labeled ‘colon’ and consists of a segment of bowel measuring 13cm in length after fixation. The sample is surrounded by a moderate amount of pericolonic fat. 3cm from one resection margin is an ulcerated round tumor measuring 3.2cm in diameter. The rest of the mucosa is grossly unremarkable."

This tells us the sample was a 13cm long piece of the colon, with a tumor found 3cm from one end.

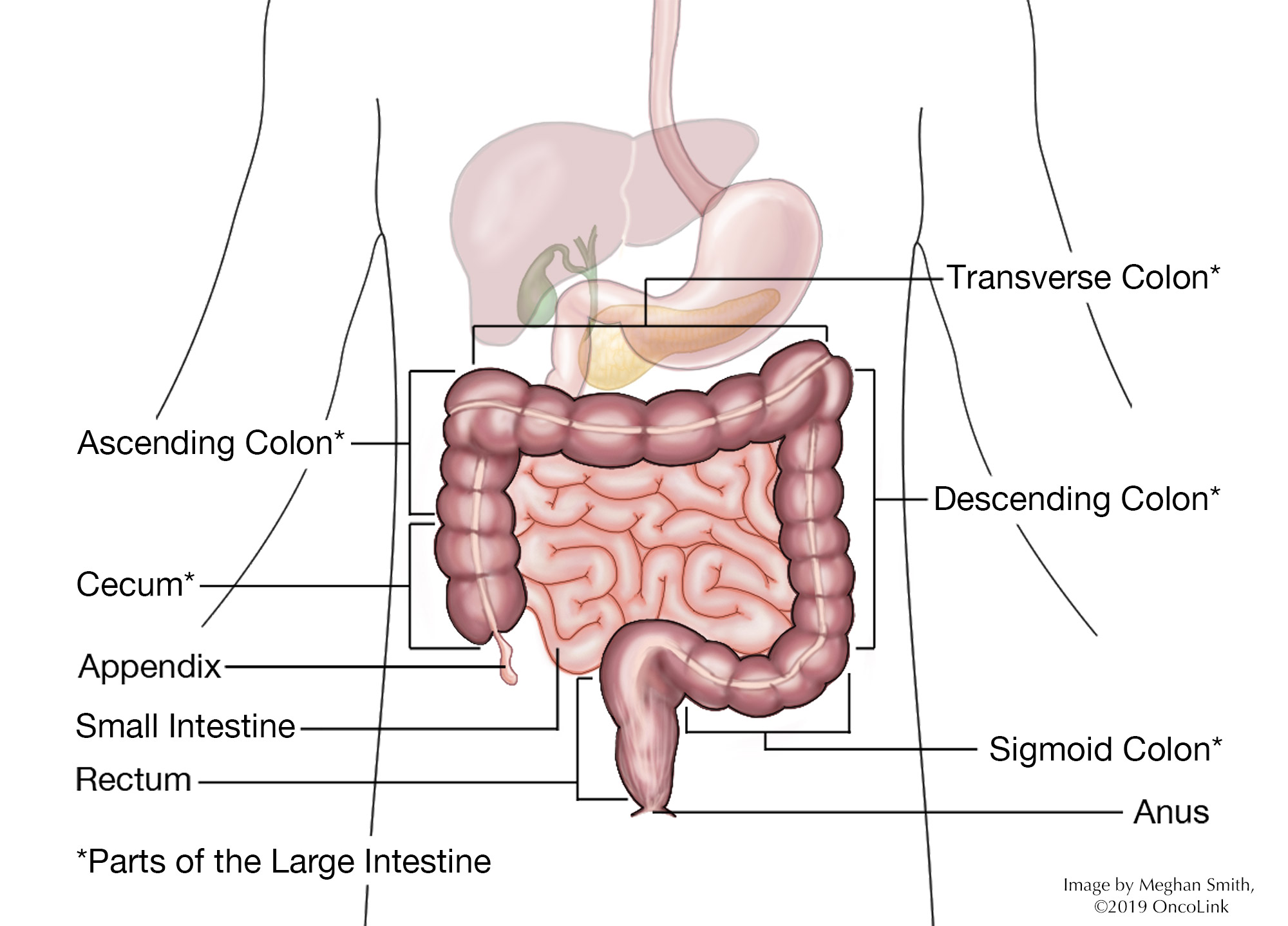

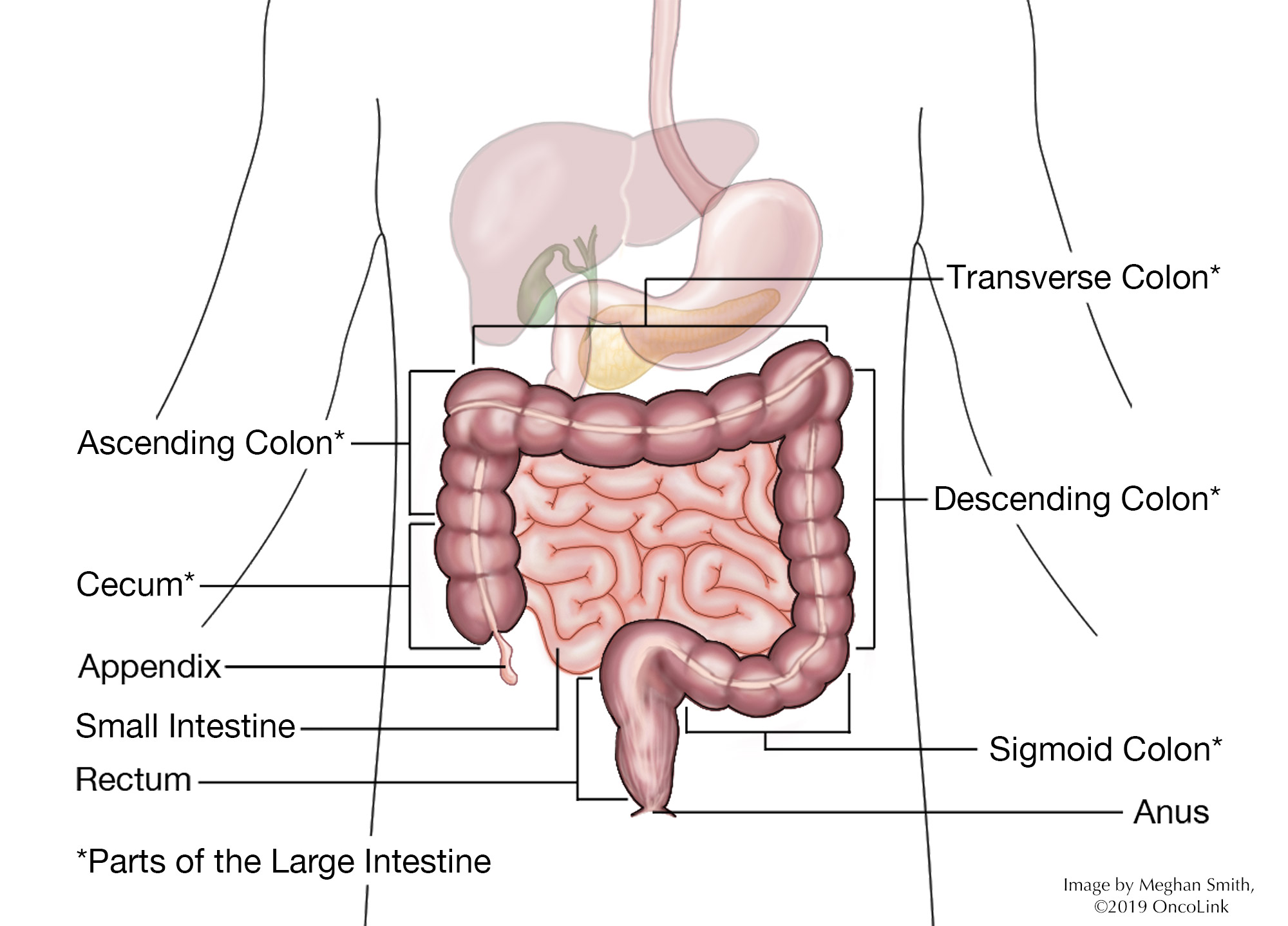

We need to know more about the colon to understand this part. The colon, or large intestine, is a tube that is about 5 to 6 feet in length; the first 5 feet make up the colon, which then connects to about 6 inches of the rectum, and ends with the anus.

The colon is made up of several sections. Your report may state which section the tumor was in. These sections are called the cecum, ascending, transverse, descending, and sigmoid colons, rectum, and anus (see diagram). The splenic and hepatic flexures are where the colon bends (or flexes) that are named for the organs they are near.

The colon, which is shaped like a tube. It is made up of many layers, starting with the innermost layer, the mucosa (made up of epithelium) and then the lamina propria and muscularis mucosa. This is surrounded by the submucosa, which is surrounded by two layers of muscle (or muscularis), and lastly, the serosa layer, which is the outside layer of the tube. The outside of the colon is covered with a layer of fat, also called adipose tissue, which contains lymph nodes and blood vessels that feed the colon tissue.

The type of colon tumor describes which type of cells the tumor comes from. There are many different types of colon tumors:

The following tumor types make up 2-5% of cancers found in the colon. These tumor types are not discussed in this article:

A colon polyp is a benign (noncancerous) growth. Over time, polyps can turn into cancer. For that reason, they are removed during a colonoscopy and may be sent to the pathologist to decide what type of polyp it is. There are several types of polyps that can be found in the colon:

Colon polyps come in two forms:

As normal cells develop, they "differentiate" to become a specific type of cell. Histologic grade describes how closely the tumor cells look like normal cells. The more a tumor cell looks like a normal cell, the more well-differentiated it is. On the other hand, the more cells do not look like normal cells (higher grade), the more aggressive they are. They can grow and spread faster. Histologic tumor grade is broken down as follows:

When the pathologist looks at the sample of the tumor and nearby tissue, they look at the tiny blood vessels and lymphatic drainage to see if any tumor cells have grown into them. This is called lymphovascular invasion. This may be a sign of a more aggressive or advanced tumor. This is not the same as cancer cells that are found in the lymph nodes.

A tumor that has not invaded the surrounding tissues is sometimes called "in situ,” while tumors that have penetrated surrounding tissues are called invasive. T stage is classified as:

Some examples include:

The lymph system can be thought of as the "housekeeping system" of the body. It is a network of vessels (tubes) that connect the lymph nodes. These nodes have cells that clear bacteria and other foreign debris from the body. Lymph is a watery liquid that flows between cells in the body, picking up debris and taking it into the lymph node for filtering and finally to the liver where it is eliminated.

Cancer cells use the lymph system as a first step to traveling to other areas of the body. During colon cancer surgery, many lymph nodes are removed and checked to see if there are cancer cells in them. This will be stated in the report as the number of lymph nodes that had cancer cells and how many were examined. For example, the report might state "fifteen benign lymph nodes (0/15)" or "tumor seen in sixteen of twenty lymph nodes (16/20)."

It is not uncommon to have as many as 30 lymph nodes removed during a colon cancer surgery. This is different from many other types of cancer, where far fewer nodes are removed.

This is the area at the edge of the sample that the pathologist looks at. During surgery for cancer, the surgeon tries to remove the whole tumor and some normal tissue surrounding it. This area of "normal tissue" is important because any stray cancer cells may be included in this. If the edge (or margin) contains tumor, there may have been cancer cells left behind. The goal of surgery is to achieve a "clear margin,” that is, clear of any cancer cells.

All of these pieces are used to determine the stage of the cancer and what treatment is needed. By understanding the basics of the report, you will be better able to talk about your treatment options with your healthcare team. You can learn more about colon cancer staging and treatment here.

A molecular marker is something found in the blood, tissue, or other body fluid that is a sign of a normal or abnormal process, condition, or disease. There are substances in some tumors that can gauge the risk of the cancer coming back after treatment (prognostic marker) or predict a response to cancer treatment (predictive marker). Two molecular markers found in colon cancers are "microsatellite instability" and "18q loss of heterozygosity."

Microsatellite DNA is made up of nucleotide sequences, repeated over and over and linked together. It is found in all human genes. Molecular testing can find instability or mistakes in the microsatellite DNA of tumors. One type of change is the number of repeat sequences. This is called microsatellite instability (MSI). MSI is a way to measure a deficiency of mismatch repair (MMR) in tumor DNA. A deficiency of MMR causes more mutations within the colon cells. This may influence the development of colon cancer.

MSI testing identifies tumors as MSI-H (i.e. MSI-high), meaning they lack MMR proteins or are deficient in MMR proteins (dMMR), or MSI-stable and MSI-low, meaning they are considered MMR proficient (pMMR) or contain most or all of the MMR proteins.

There are two reasons to test colorectal cancers for MSI.

Humans have 23 pairs of chromosomes, for a total of 46 chromosomes, found in each cell in the body. Each chromosome has over 1000 genes. Over your lifetime, you can develop damage to genes or chromosomes due to exposures, such as smoking and viruses.

Other molecular markers being studied include chromosome 18q, KRAS, BRAF, a tumor suppressor called guanylyl cyclase 2, p53, and ERCC-1. Studies have found some of these markers to be useful in determining cancer treatment. For instance, anti-cancer medications that target the EGFR protein, such as cetuximab and panitumumab, will not be effective in people who have a KRAS or BRAF gene mutation (defect). These tests are not the standard at this time, but some providers are using them, so you may hear them described to you.